By

Image Source: Adobe Stock

Whit Remer says when he was working and living in the Washington, D.C. area a decade ago, he reached out to then Tampa Mayor Bob Buckhorn with a recommendation: the west Florida coastal city should create a high-level position focused on sustainability and resilience, given Tampa’s location and the frequency with which it must confront severe inclement weather.

“‘And by the way, I’ll fill it for you,’” Remer says he told Buckhorn. “He didn’t bite, but I ended up moving down to Tampa through another job.”

Remer, who studied environmental law and urban planning in New Orleans after Hurricane Katrina struck in 2005, worked for an insurance research organization when he moved to Tampa. The company’s focus was to build full-size houses and subject them to simulated storms and other foul weather elements – think crash test vehicles, where data is used to improve the safety of passengers. Based on the results of the storm-battered test homes, Remer’s company could determine what types of building codes could better protect people and property from future natural disasters.

After Jane Castor was elected Tampa’s mayor in 2019, Remer circled back and made a similar pitch to the one he’d proposed years earlier. Remer says Castor became immediately interested and “started asking more questions.” This time around, the mayor’s office created a position based on Remer’s recommendations.

Then Castor asked Remer to fill it.

Remer is part of a fast-growing field in cities around the country, particularly those vulnerable to natural disasters, like Tampa. He is a member of the Southeast Sustainability Directors Network, and he and his counterparts in other communities have become important voices in how cities evolve and adapt to severe climate events going forward.

“It’s important work, and I don’t think the underlying causes of it are going away – whether that be stronger and more intense storms, poor community planning, or (ineffective) building codes,” says Remer.

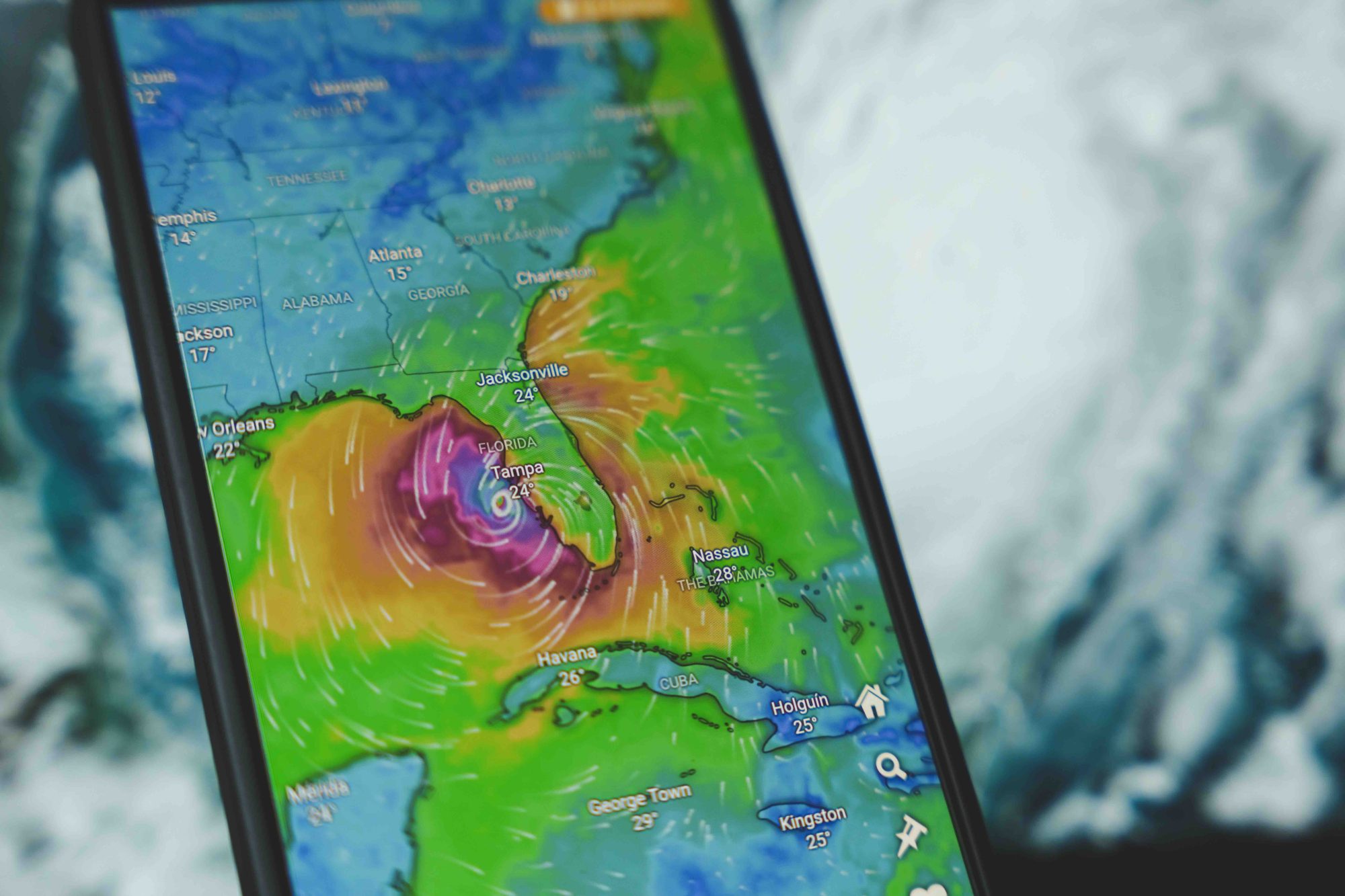

During his four years on the job, Remer has already witnessed firsthand the devastation caused by natural disasters. Hurricanes Helene and Milton struck the Tampa region last year within two weeks of each other, and Hillsborough County (which includes Tampa) alone suffered an estimated $1.8 billion in residential damage after Helene.

But Remer says that he was encouraged by many facets of Tampa’s response to the storms. He cited the city’s preparedness prior to the hurricanes’ landfall and lauded Tampa’s solid waste teams and other city workers who labored tirelessly for weeks after the storms had passed.

“If you don’t have a well-oiled machine, those [situations] can turn into public health crises and can sink your economy, especially here in Florida, where economies are heavily dependent upon tourism,” he says.

Image Source: Adobe Stock

When Remer accepted his current post, there was already a plan in place for a $2.2 billion pipe replacement program for water and wastewater treatment. “These are good infrastructure investments that I look at, tweak here and there,” says Remer. His efforts help ensure that resilience and sustainability are part of any such blueprint.

When Mayor Castor hired Remer, one of her first orders of business was to assure Remer that he would have broad authority to carry out his work. He’s paid by the city and reports to Castor.

“Castor’s vision was, ‘If we’re going to really move the needle on sustainability and resilience, you [Remer] need to have a citywide reach,’ and not be singularly directed by a particular department,” says Remer. “That helped me stand out in the field a little.”

Remer’s office leads efforts on many fronts, including changes and updates to building codes and requirements that new housing structures be built with materials that are not only modern but more durable and resistant to powerful weather systems. Remer’s office has access to state and federal money, which can be a difference-maker in circumstances when he meets resistance.

“There are literally hundreds of billions of dollars for sustainability projects right now,” he says. In the last five years, Remer has been able to secure approximately $80 million between state and federal resources and funnel that capital into sustainability/resilience projects.

Those projects might include the installation of solar panels on a building or a community bioswale – a vegetated channel that filters stormwater runoff – in place of longer, bigger pipes. And when Remer offers the incentive of a federal grant to pay for the changes, “that always helps the conversation.”

Len Simonian says that he and his wife Kristy built their Malibu home in 1997 and moved in a year later. Over the next two decades, they set down permanent roots and raised three kids in the idyllic Southern California community that overlooks the Pacific.

Like many California residents, the Simonians knew there were risks to living in that region of the country.

“You have to go in with your eyes open,” says Simonian, 56. “It comes with the territory – earthquakes and wildfires. But you never think it will happen to you.”

When the 2018 Woolsey Fire raged through Los Angeles and Ventura counties (the former includes Malibu), nearly 100,000 acres burned, and over 1,500 structures were destroyed, including the Simonian home. The family had evacuated safely with their pets and essential belongings, but they lost everything else in the fire.

In the aftermath, while some of their Malibu neighbors chose to leave and relocate, the Simonians never had any doubts that they would stay and rebuild. Getting to that stage, however, presented many challenges.

“First, it’s a general shock. It’s chaos. We didn’t know if our house had burned for two or three days,” says Simonian. “You then hear all of these things, ‘Call FEMA (Federal Emergency Management Agency), call your insurance.’ They set up resource centers in Malibu. It was a tangled web of rules and regulations.”

Between the debris removal and securing a permit to rebuild, Simonian says he feared a lengthy, bureaucratic wait. “All of a sudden, the city got 400 permit applications,” he says.

Yolanda Bundy emerged as a stabilizing force when Malibu began its recovery effort. Bundy, who holds degrees in civil and structural engineering, had already worked in the city of Ventura’s Building and Safety Division since 2008 and had helped that community rebuild after the 2017 Thomas wildfire. In addition to her credentials and experience, Bundy says she brings a bedside manner to her job, a trait she says “goes a long way” with people who face these ordeals.

Image Source: Adobe Stock

“My role in this jurisdiction is something that needs to be considered as a requirement when hiring a building official or people that are going to help,” says Bundy. “Destructive fires – it’s the same story over and over, stories of loss and heartache for the whole community. One thing that I’m blessed to have is the ability to listen with the heart. People feel that a genuine person can give them hope and calm during desperation.”

When she was brought to Malibu to be the city’s environmental sustainability director and chief building official in 2019, one of her most important contributions after the Woolsey Fire was to expedite the building permit process.

“We got our permit in about 14 months,” says Simonian. The family was able to rebuild on the exact footprint of their previous home, but more importantly, they implemented numerous safety measures to help protect the family and the structure against future wildfires: No more vegetation near the home itself; no mulch or wood chips used for landscaping; a hose hooked up to their 30,000-gallon pool and a backup generator as a defense strategy in case of a power outage during a fire; installation of roof vents that face south, the opposite direction of the path of dangerous Santa Ana winds.

Simonian says the Malibu community as a whole put on a united front to rebuild, and that the support for local businesses was overwhelming in the aftermath of Woolsey, further underscoring Malibu residents’ advocacy for sustainability. When the Franklin Fire swept through Malibu last year, Simonian says he thinks the city was better prepared this time – improved communications, coordinated evacuations, and set evacuation zones – lessons undoubtedly learned from the Woolsey tragedy.

Tornadoes ravaged Oklahoma City and the surrounding region last November, and according to PowerOutage.us, approximately 99,000 Oklahoma homes and businesses lost power.

Since it was established in 1993, the Oklahoma Department of Environmental Quality (DEQ) has been instrumental in helping the state’s communities rebound from these types of disasters, and the role of sustainability within the agency’s efforts has grown exponentially as officials and civic leaders plan for the future.

“The DEQ has an important role in helping Oklahomans navigate through natural disasters, from the immediate aftermath to months down the road when repairs are complete,” says Rob Singletary, the DEQ executive director.

Power outages and water line breaks are the most common effects of tornadoes, and like in Tampa, one of the first responses by officials in the immediate aftermath is to “assess damage to water and wastewater systems,” according to Singletary. The DEQ’s Environmental Complaints and Local Services division works in conjunction with local officials in these efforts.

“The ECLS staff will then work with DEQ’s Water Quality Division (WQD) enforcement staff to provide technical assistance to local officials about how best to implement short-term measures to address problems,” says Singletary. “This includes interfacing with Emergency Management officials who can provide resources to affected communities. It is important for DEQ staff to coordinate with EPA (Environmental Protection Agency) and other federal agencies, serve as the primary source of expertise on industrial and commercial waste, provide information pertaining to open burning regulations to citizens and communities, offer technical assistance to homeowners in regards to their septic systems, and work with communities for their debris disposal needs.”

Singletary points out that the DEQ’s communications and education department is the agency’s principal arm to inform the public after a natural disaster. “It is important for the public to have accurate, factual information on a wide array of topics, including boil orders (to ensure clean water), debris removal sites, and best practices for cleanup and safety measures,” he says.

Finding insurance carriers who will offer fire, flood, or other natural disaster coverage has become increasingly difficult for residents in those communities affected by such events. The climate change issue has only intensified the debate over what a homeowner can and cannot file in a claim.

“Insurers are becoming much more specific with the types of things that they underwrite,” says Remer, the Tampa official. “The insurance market has been unstable. People were using insurance as a kind of warranty. What we’re seeing now is insurers are moving toward a funder of last resort. Deductibles are so high, you really want to think twice before filing a claim.”

Remer says that there are state alternatives individuals can explore when they begin rebuilding.

“With the My Safe Florida Home Program, if you install $5,000 impact-resistant windows, the state will give you $10,000 in return. The state is paying people to mitigate damage and hazards to their houses,” says Remer. “In the long run, I do think Tampa/St. Petersburg and other coastal areas in this country are such that we don’t have to pull back and do a managed retreat. We have another 50 years before the projections here [say] sea levels will rise and will start impacting infrastructure and impact the quality of life. We can live here safely and successfully. But we’ve got to build the right infrastructure and put the right systems in place to do so.”